The healing power of nature

By Siba Sahabi

Contact with nature has a positive influence on the way our brains process information. Just being in nature stimulates recovery in times of stress and illness. Nature gives us the unconscious message that we have the right to relax. Scientists call this phenomenon the ‘restorative effect’. In this article, we will examine how this effect can be used in a modern hospital.

Love of nature

There is a special term that expresses the relationship between man and nature: biophily. Biophily literally means ‘love of life’. This Ancient Greek word comprises the two terms bios (life) and philia (love). The term describes the human need to be in contact with nature. Research supports the utility of this love. Under the influence of nature, we experience fewer negative emotions like stress, fear, and anger. Simply through contact with nature, patients experience less pain and need fewer painkillers. In the most positive case, experiencing nature sets a quicker recovery in motion and results in a shorter hospital stay. How long have we known that nature has such a tremendous influence on our emotions and health? And how can its ‘restorative’ effects be incorporated into healthcare?

Tree #2 by Myoung Ho Lee, archival inkjet print, 2006 ©

Myoung Ho Lee, photograph courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Tree #2 by Myoung Ho Lee, archival inkjet print, 2006 ©

Myoung Ho Lee, photograph courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New YorkThe Persian garden

Since ancient times, it has been considered as obvious that nature should be given a role in a patient’s treatment. For example, in the Persian Empire, a special kind of garden was developed. The so-called ‘Persian garden’ — also called an ‘Islamic garden’ or ‘Arabic garden’ — is characterised by a 3,000-year-old tradition and symbolises paradise on earth. Fun fact: The word ‘paradise’ originally comes from the Ancient Persian word pairidaēza, which means ‘fence’ or ‘enclosed park’.

In the middle of a Persian garden, you will find a fountain (which makes relaxing sounds), surrounded by a number of little benches where you can sit and rest. The water flows out of the fountain through four narrow canals going in different directions. Not only does it look beautiful, the canals also serve a practical purpose, providing water to the surrounding plants. The Persian garden is associated with vitality and rebirth, both for healthy people and for the sick.

Viridaria

In Europe, starting in the Middle Ages, monastic gardens for people with physical and psychological complaints were made available. These gardens, called monastic because they were found in monasteries, emphasised hospitality and love for one’s fellow man. These rectangular gardens were usually located in the middle of a building complex. The planted courtyards were surrounded by four walls with features that included beautiful arcades called cloisters, and they were equipped with a central water well. On hot days the arcades provided cooling shade, and when it rained they provided dry areas outside.

Monastic gardens also have a medicinal function. From a historical perspective, they have had a tremendous influence on the development of Western medications. In the herb garden, the so-called ‘herbularius’, plants with medicinal properties were grown. In Central European monastic gardens, plants from the Orient and Southern Europe, such as fennel and lovage, were integrated into Western medicine and studied in depth. Nuns and monks obtained their knowledge from their own experience. They also read and copied the books of ancient authors and then shared their knowledge, plants, preparations, and seeds with other monasteries. So you might say that the monastery functioned as a sort of laboratory.

The secular pharmacy, which began to expand in urban settings in the 14th century, applied the knowledge and concept of the monastic gardens. In this way, pharmacies gradually replaced the function of the monastic gardens. In the 16th century, a large number of herb books with precise descriptions and categories were published by monasteries. While that was happening, botanical gardens were being created at universities that taught medicine. These gardens prolonged the tradition of the monastic gardens and integrated exotic medicinal herbs into educational settings.

Tree...#6 van Myoung Ho Lee, archival inkjet print, 2013 © Myoung Ho Lee, photograph courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

The pavilion model

In spite of the development of medicines, in the period between 1750–1900 not enough medicines were known that could be used to treat various illnesses that patients had. Knowledge was also lacking in the area of surgical treatments. For this reason, attention was paid to specific diets and ‘manipulating’ the patient’s surroundings. The so-called pavilion model was developed in this period. This model consists of various small recovery buildings on a larger estate, often designated for a particular category of patient and designed for a specific social class. These pavilions were detached from each other in a parklike landscape. Two advantages of the pavilion model were that patients could experience nature and that it limited cross-infection between patients. Disadvantages included the fact that the building complex required a large parcel of land and that it took hospital staff longer to get there.

In the 20th century, germ theory was developed, along with diverse and improved medical technologies, medicines, and new operation techniques. The discovery of penicillin made the structure of the pavilion model unnecessary, because the problem of cross-infection between patients had become less serious.

The healing power of green

Large hospitals that were starting to spring up in the 18th century were characterised by their institutional character. The attention was mainly given to modern treatments rather than to a stimulating environment. Medicine had lost sight of the healing power of experiencing nature, until 1984 when architect Roger S. Ulrich demonstrated, in his studies, the healing effect of ‘green’ on patients’ recovery. According to him, oxygen, the fresh scent, and even just the sight of trees and plants (either real or depicted) were beneficial. His publication was groundbreaking and opened the doors to the reintegration of nature into healthcare, stimulating a new school of design called ‘Evidence-based Design’. EBD is a school of design where design decisions are based on scientific research. The research investigates and stimulates positive links between the hospital environment and the patient’s health.

Tree #3 by Myoung Ho Lee, archival inkjet print, 2006 ©

Myoung Ho Lee, photograph courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery, New York

Tree #3 by Myoung Ho Lee, archival inkjet print, 2006 ©

Myoung Ho Lee, photograph courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery, New YorkReintegration of the healing gardens

We now know that looking at nature can lead to a substantial reduction in stress in less than five minutes. For this reason, a large number of Dutch hospitals were equipped with ‘green zones’. Unfortunately, we cannot speak of ‘gardens’ here, and these green zones are often not even accessible to patients, visitors, and hospital staff.

The Tergooi Hospital in Hilversum shows how it can be done: during their treatment, cancer patients can sit in a specially designed pavilion in the hospital’s garden. The wooden pavilion has a glass ceiling, and the open structure stimulates experiencing nature with all its positive effects on a patient’s well-being.

Think of how great it would be to integrate a piece of ‘paradise on earth’ into all modern hospitals! A Persian garden. With a fountain gurgling softly in the middle, surrounded by places where you can sit and relax. A green environment where you can look at plants and flowers, either alone or with those close to you. A place the evokes pleasant thoughts and healing feelings.

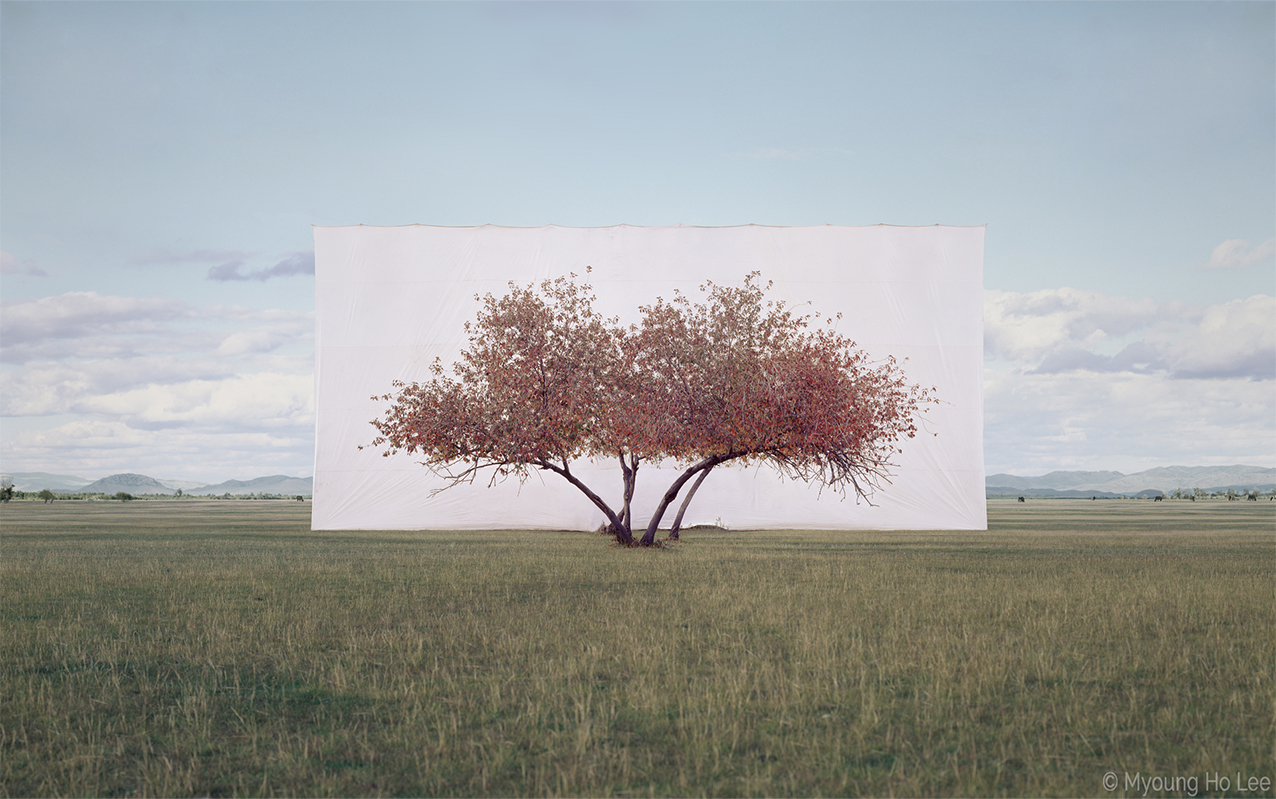

Tree…#2 by Myoung Ho Lee, archival inkjet print, 2012 ©

Myoung Ho Lee, photograph courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York. Myoung Ho Lee photographs solitary trees framed against white canvas backdrops in the middle of natural landscapes.

Tree…#2 by Myoung Ho Lee, archival inkjet print, 2012 ©

Myoung Ho Lee, photograph courtesy Yossi Milo Gallery, New York. Myoung Ho Lee photographs solitary trees framed against white canvas backdrops in the middle of natural landscapes.