Moirai

How do we perceive time? Does the way we perceive time become altered in an environment such as a hospital? How can we improve the way patients and visitors experience waiting? What possibilities and limitations do you encounter when you share your space with other patients?

This website shows the results of my research. By involving various disciplines such as philosophy, psychology, art, theatre, architecture, and design, the relation between time and hospitals is placed in a broader context.

I have named the project after the Moirai, the Three Fates of Greek mythology that together determine a person’s fate. (Moira is an Ancient Greek concept meaning something like destiny, fate, or share.)

The three Moirai – Clotho, Lachesis, and Atropos – represent the three stages of life: birth, life, and death. In this Greek myth, time is symbolised by a thread: Clotho spins the thread of life, Lachesis measures it, and Atropos cuts it. With this project, I want to influence the fate of the waiting patient in a positive way.

All the text has been translated into both English and Arabic. English is the most frequently spoken working language amongst foreigners and immigrants, while Arabic is spoken by a vulnerable group in our society– legal residents and refugees from the Middle East. By making this website trilingual, I hope to stimulate inclusiveness.

Siba Sahabi – editor in chief

Acknowledgements

Acknowledgements

The Moirai project was made possible with the financial support of the Creative Industries Fund NL.

My special thanks go to psychologist and writer Marcelino Lopez, who has guided the Moirai project from beginning to end and has contributed a couple of articles. His feedback was quite valuable and decisive for the process.

I would like to thank graphic designer Thijs Verbeek and documentary filmmaker Chris Rijksen for their creativity, expertise, and commitment. They have taken all the research results and put them into images, text, and sound in both the accompanying magazine and the series of podcasts entitled De Wachtruimte.

I wish to thank the Albert Schweitzer hospital, the Amsterdam UMC – Locatie AMC and architectural historian Cor Wagenaar for their substantive contributions.

Leston Buell and Ahmed Gad produced professional translations of all texts into English and Arabic.

I would also like express my heartfelt thanks to the following writers, designers, and artists for their valuable and inspiring contributions: photographer Arjan Benning, AtelierNL design studio, artist Christiaan Bastiaans (courtesy of kunstcollectie AMC), font designer Lara Captan, photographer Ellie Davies, philosopher Laurens Landeweerd, Druid theatre company, designer Sanne van de Goor, Humans sinds 1982 design studio, photographer Myoung Ho Lee (courtesy of Yossi Milo Gallery), photographer Anna Orłowska, font designer Kristyan Sarkis, illustrator Joost Stokhof, journalist Anita Twaalfhoven, and designer Nel Verbeke.

And finally, I am tremendously grateful for the following patients and hospital staff for sharing their personal stories and experiences: Eva, Kristel, Cor-Jan, Edmee, Pieter en Erwin.

How do we perceive time?

And how does the way we perceive it change in an environment such as a hospital?

In our six-part podcast, patients and hospital employees tell their personal stories about a major experience in their life and how time plays a role. Here are three short introductions to some of these special stories:

– What happens to you when you are told at a relatively young age that you have cancer? How does an intensive treatment process change your perception of the past, the present, and the future? Kristel, who was diagnosed with breast cancer at the age of 30, takes us on her journey.

– What is it like when you are born as a girl but feel more like a boy? How does your life change when you take your fate into your own hands and decide to transition? At 47 years of age, Cor-Jan has decided to take this step and tells about his healthcare ‘waiting experience’.

– How can you help patients get through their time in the hospital as pleasantly as possible? Eva works with children as a nurse and explains how she supports them and their parents when things become really difficult.

The Dutch-language podcast De Wachtruimte (The Waiting Room) is produced by documentary film-maker Chris Rijksen. The interviews were prepared in collaboration with artist Siba Sahabi and psychologist Marcelino Lopez.

Time in the brain

The Relict of Time by Nel Verbeke, kinetic installation, photography: Alexander Popelier, 2017. The small half bowl in the middle of the wall object rotates at regular intervals. This causes a small quantity of black dust to fall onto the copper plate, and in this way the installation makes the fleeting nature of time visible.

The Relict of Time by Nel Verbeke, kinetic installation, photography: Alexander Popelier, 2017. The small half bowl in the middle of the wall object rotates at regular intervals. This causes a small quantity of black dust to fall onto the copper plate, and in this way the installation makes the fleeting nature of time visible.How your brain makes and distorts time

By Marcelino Lopez

An hour in a traffic jam can feel like an eternity, while a lazy Sunday with your sweetheart can go by like a flash of light. How is it that you can experience the same duration of time in such different ways? The reason is that, in a certain sense, time is created by your brain.

Time is a funny thing. Though you probably don’t doubt the existence of time, you can never actually observe it. Looked at subjectively, the time is always ‘now’. You can only deduce the existence of time from the fact that your perceptions are constantly changing and that you can remember them. Now you’re reading this sentence, and in a moment you’ll be reading the next one. One moment you’re thinking of your mother, but the next moment your mind is on your next appointment.

Time as you experience it is constructed in your brain in a most ingenious way. We may take our ‘healthy’ sense of time for granted, but it is actually quite extraordinary. I don’t need a clock or a calendar to determine that I am writing this on an early spring morning and that I’ve been working on it for about 10 minutes. How does my brain do that?

The perception of time is a complex process in your brain, with different parts of the brain working together to give you a coherent sense of time. Anyone who has used psychedelic drugs knows just how radically this process can be disturbed. What’s more, under the influence of drugs, one’s perception of time can disappear altogether.

In this two-part article, we first look at the factors that create and influence your perception of time: why does time seem to go by so slowly when you’re unhappy, while it flies by in a moment of happiness. In the second part we examine whether we can manipulate our sense of time in such a way that we spend less time being unhappy and more time being happy.

Estimating time without a watch

Even physicists find time difficult to define, but for the purposes of this article we need only distinguish between objective and psychological time. We can measure objective time by following the hands of the clock as they tick by. This kind of time is exactly the same for both you and me. In contrast, psychological time is subjective and says something about how you and I experience that objective time: this is what psychologists call time perception. How does your brain know approximately how much time has passed between the moment that you woke up today and now?

Our whole universe, including your body, is regulated by predictable, cyclic rhythms: day and night, ebb and flow, the four seasons, your breathing and heartbeat, and your sleeping/waking rhythm. All those rhythms give us indications of time. In particular, our body’s internal 24-hour clock – known as our circadian rhythm – helps us determine the time. This biological clock is driven by a small region of the brain called the hypothalamus. Following a 24-hour rhythm, the hypothalamus emits certain hormones that regulate our blood pressure and body temperature to put us to sleep, wake us up, and give us a sensation of hunger.

The surprising thing is that the circadian rhythm is actually 24 hours and 11 minutes long, but this discrepancy gets corrected by other factors such as daylight. In experiments where people spend long periods of time in an isolated space with neither natural nor artificial signals indicating time (such as daylight or clocks), a person’s biological clock gets completely off track. In these sorts of experiments, people eventually end up with a circadian rhythm of 50 hours.

To estimate how much time has elapsed, your brain uses the biological clock and natural rhythms as a frame of reference. Furthermore, all events are full of indicators of how long something lasts. Walking to the shed takes ten seconds, listening to a song takes three minutes, a workout takes one and a half hours, a holiday lasts two weeks, and so forth. Your brain intuitively compares an event (a walk to the supermarket) with your natural rhythms and with past events, allowing you to make a realistic estimate of approximately how much time has gone by in seconds, minutes, hours, days, weeks, and years.

It should come as no surprise that this intuitive way of estimating elapsed time is not as accurate as your watch, especially when it comes to longer periods of time. Consider these research results:

When people aren’t actively conscious of it, it only takes them 55 seconds to estimate that a whole minute has gone by. This estimation of one minute is relatively stable. Estimations for longer periods, such as an hour, are more fickle and less accurate, especially if the biological clock has been tampered with. After spending a long time in an isolated space with no time signals, test subjects ended up with a circadian rhythm of 50 hours and assessed one hour as two whole hours – twice as long as they would have under normal circumstances. Nothing changed in their estimations of a single minute.

Your sense of time depends not only on what you perceive – such as the difference between an exciting thriller and a boring lecture – but also from the state your body and your mind are in.

For example, your body temperature has considerable influence on how you perceive a single hour. Research shows that a few degrees more or less can speed up or slow down a person’s sense of time by 20 percent. For this reason, a patient with a fever will perceive one hour as going by more quickly than they normally would. This may be due to the fact that the speed of chemical processes in our body influences our sense of time.

Another good example of how time gets distorted is during an acute crisis situation. People involved in a traffic accident often perceive the couple of seconds before the collision as much longer. With an impending crash, your body produces a jolt of adrenaline, making your brain work faster and record more impressions per second than normal. On the other end of the spectrum, you have experiences where nothing exciting occurs, such as a traffic jam. In those situations, time seems to tick by much slower than usual.

According to scientists, time perception functions like a U-curve. The two extremes of the curve – consisting of extremely stimulating or very unstimulating periods – are where time usually slows down the most. In between those extremes you can assume the following ‘law’:

The more that is happening either in your brain or around you, and the more attention and processing time your brain needs, the faster time seems to go by.

Knitting Lamp by AtelierNL, photography: Paul Scala. The lampshade consists of a knitting machine which is activated once the light is switched on.

The paradox of our sense of time

When little or nothing seems to be happening, we have the impression that time goes by much more slowly. In calm environments and in the dark, time seems to go by more slowly than is really the case. The more engrossed we are by the environment or the task at hand, the faster time seems to go by.

New experiences and unfamiliar environments speed time up. Just compare a weekend at home with a weekend away in an unfamiliar city. Home is familiar territory, where your brain is working on autopilot, whereas an unfamiliar city is new and demands your attention. But there is also a paradox in our perception of time.

Time flies when you’re having fun, but when your weekend away is over, it seems to have gone on longer than your usual weekend at home. What’s going on is that events in the past are remembered differently from how they are experienced.

Time appears to pass more quickly when you are having fun and having new experiences, but afterwards you remember that time as being longer than how it felt during the moment you experienced it. Why is that? The memories of a predictable weekend at home occupy little space in your memory because they resemble all your previous weekends at home. On a weekend at a new location, your memory creates a large number of new memories, using much more space in your brain. The coffee, the hotel room, the receptionist, the streets, the people you see: everything is new to you. Not only does a weekend away present you with a large number of new stimuli, afterwards you have the feeling that the weekend lasted much longer.

This explains why time seems to go by more quickly as you get older. When you’re young, many experiences still feel new, exciting, and instructive. The older you are, and the more experiences you have had, the less interesting those experiences are to your memory. Our memory is sensitive to the so-called novelty effect. We remember stimuli that are new or different much better than those that are already familiar.

Do you want to be happier in the here and now? And create happy memories in the process? Seek out activities that demand your attention and that allow you to learn or experience something new each time. Psychologists have discovered that people are happiest when they are engrossed in the activity they are engaged in. Psychologists refer to this state as ‘flow’. Dancing, painting, and surfing are just a few examples of activities in which people can experience this ‘timeless’ state. You experience flow when you are focused on a goal in the here and now that demands your complete attention. That focus gives you the ability to become one with what you are doing and to forget all sensation of time. What is needed is a physical or intellectual activity that is suited for your skills but pushes you to your limits. So, it should be just short of being ‘too difficult’. Flow has more or less the same effect on your brain as cocaine. People who engage in these sorts of hobbies possess a powerful ‘instrument of happiness’. Having your attention completely focused on something – and forgetting about time – will make you happy.

Marcelino Lopez (1974) is a Dutch-Spanish psychologist, writer, and therapist. He has written two books about relationships in modern times and is currently working on a critical book on the benefits and drawbacks of the happiness industry. He is interested in moral and ethical issues and shares his insights through a variety of media: print, online, radio, and TV.

How mindfulness influences time

and mental suffering

By Marcelino Lopez

Put two random people next to each other on a park bench, and they will probably experience time in completely different ways. One of them will be reading a good book and will have lost all sense of time; the other, waiting for a blind date, is conscious of every fleeting second. In a certain sense, waiting is suffering from time.

If you are enjoying yourself, you have probably forgotten about time. You are absorbed in the moment. If you are waiting for something, you are dealing with the future. That slows time down. And the more uncertain that future feels, the slower time seems to go by. Stress, anxiety, and concern about the future make time longer.

In this article we will delve a bit deeper into the question as to how time perception, happiness, and suffering relate to each other and you can learn how to spend less time suffering and more time enjoying yourself.

Anticipation stress: waiting in uncertainty is suffering

A simple study by De Berker et al. (2016) shows how waiting in uncertainty increases suffering. In the study, 45 test subjects were each presented with a pile of stones on their computer screen. They had to guess whether there was a snake hiding underneath. If there was, the test subjects could expect to receive an electric shock. The research tested how much stress they experienced. Participants were divided into two groups: half of them knew beforehand that they would receive a shock, while the other half did not.

The unequivocal conclusion: participants experienced much more stress when they didn’t know whether they would receive a shock. Being certain, even if the outcome is negative, is less stressful than living in uncertainty.

For this reason, waiting for the outcome of a medical test is often more stressful than actually getting the diagnosis. If the outcome has been determined, that calms your brain, even if that outcome is negative. You know what you’re dealing with. Tension comes about in the uncertainty of not knowing. Research also shows that test subjects who receive a false diagnosis or a false explanation for their pain experience less pain than patients who received no diagnosis or explanation at all.

The value of stress

It is thanks to this sort of research that people are, by nature, relatively bad at managing uncertainty and ‘the stress of waiting’. There is also a paradox: optimists whose positive outlook allows them to experience less stress while waiting actually react more strongly to bad news and less enthusiastically to good news. In contrast, ‘stressed waiters’ get a boost from good news and get less upset over bad news. So, anticipation stress is not merely bad.

Why are we so bad at dealing with uncertainty? Your brain has evolved to help you survive and, even if you’re not conscious of it, is constantly ‘telling’ your body what it needs to do. In an unclear situation it can’t do that, but since doing nothing can potentially be fatal or detrimental, your body produces stress hormones to prepare itself for imminent danger. This is why you feel more alert and tense than normal if you walk around an unfamiliar neighbourhood at night. Even if you know that in all likelihood nothing is wrong, the fact that the place is unfamiliar makes you keep your guard up more than usual.

So, we could also call stress the ‘urge to do something’. The hormones that provoke this feeling of urgency are cortisol, adrenaline, and noradrenaline. Produced in the adrenal cortex, these substances immediately make you alert, focused, and ready for action. They accomplish that by doing things like raising your blood pressure and activating your nervous system. Stress is quite a healthy reaction, but it becomes problematic if it goes on for too long and does not alternate with periods of rest and relaxation.

When stress becomes chronic

Humans are the only animal capable of thinking about the past and the future. This talent for looking ahead and planning gives us more power and control over our fate than other species, but the price we pay for this time perception is that we can also be chronically worried and unhappy. If we don’t learn how to rein in our creative mind, our thoughts very quickly start playing tricks on us.

Even if we’re sitting on the sofa with a warm blanket and our favourite beverage, we can become totally upset merely due to our thoughts. With a little bit of effort, you can think up an endless number of horrific scenarios for things that could go wrong tomorrow. Maybe the milk has dangerous bacteria in it. The neighbour’s house might catch fire. You might get sacked from your job tomorrow.

And to make things worse, you can’t just switch off your stream of thoughts as you would your TV set. You actually have little control over that. Just like the sounds you hear and the things you see, your thoughts aren’t something you choose. They come and go the whole day long, interrupted only by sleep. A worrier will recognise this situation.

With some people, worrying can intensify so much that it leads to chronic stress, symptoms of exhaustion, and panic attacks. Psychologists refer to this as generalised anxiety disorder. The problem is usually not the environment but a brain gone wild and running in circles because there is no quick and ready solution. Many of life’s problems have no quick and ready solution. Will I still have a job tomorrow? Does my partner still love me? Do I still love my partner? Will I still be healthy tomorrow?

You can go on worrying about these sorts of issues eternally, but you’ll never get a satisfying answer to them. Our brain needs certainty, but life itself is one big pile of uncertainty. No one knows what tomorrow will bring.

The key question is: Can you learn to relax and enjoy yourself while being conscious of the fact that the future is uncertain and that life can hit you hard at times? Is there a technique for dealing with uncertainty better?

To make unpleasant and boring moments pass by more quickly, most people seek out distraction. They kill their boredom by playing a game on their smartphone or exercising. Distraction works fine for ‘light’ suffering, such as boredom or an aching back, but with major uncertainty or serious pain it doesn’t work so well. The pain demands your attention and doesn’t just let you chase it out of your consciousness. With acute physical pain, you can resort to any number of painkillers, but the drug therapy route is more controversial when applied to psychological pain. You can take tranquillisers or numb yourself with alcohol and drugs, but in the long run, the fleeting, addictive, and uncertain character of these substances creates more problems than they solve. Is there some way to approach psychological (and physical) pain without medications?

![]() Illustration by Joost Stokhof

Illustration by Joost Stokhof

Meditation: the power of rediscovering the here and now

You might call mindfulness meditation spiritual, religious, or airy-fairy, but we can also approach meditation from a scientific perspective, detached from its Buddhist origins and mystical connotations. Those aspects are not actually necessary to demonstrate its value. From a scientific perspective the verdict is clear: meditation is good for almost everything, just like sleeping, eating healthy, and walking. People who have unprejudiced awareness of the here and now – that’s what mindfulness meditation is – are doing themselves a lot of good. More than thirty years of research shows that it makes normal people like you and me much less neurotic, stressed, and anxious. And thus, happier. The advance are both mental and physical and can improve quality of life in different areas—work, relationships, love, creativity, and health. It increases concentration, improves one’s memory, and eases chronic pain. For an ‘activity’ that many people would probably dismiss as useless and utterly boring, its effect is simply amazing.

How can it have such a great effect? It’s less mysterious than it might seem. It’s a matter of silencing that worried voice in your head.

Research shows that the average person spends about half of their waking hours mulling over things, daydreaming, and worrying. You recognise it from that voice in your head that is constantly talking to you. That inner monologue in which we spend our lives is also called the brain’s backup network: the brain’s default state when it isn’t busy with something specific, but is daydreaming, making comparisons, worrying, and fretting.

Research shows that it is precisely that uncontrolled, inner monologue that makes people unsatisfied, stressed, and unhappy and keeps them in that state. The more our brain is busy digging up the past or trying to control the future, the more our attention shifts to things that aren’t going well in our life (because they need attention).

By training your attention with mindfulness meditation you create a different relationship with your inner monologue. Meditation is not about forcing yourself to stop thinking; that doesn’t work. In a certain sense, meditation teaches you to detach yourself from thoughts (and from lines running parallel to them). Not by viewing your thoughts and feelings as intruders, but rather by seeing through their fleeting and unreal nature. Over time, recognising that distinction makes a world of difference.

Skilled practitioners of meditation can testify to this. Just as with any other skill or sport, perseverance is required before meditation becomes a habit and feels good. You can train your brain in the same way that you can train your muscles. Meditating regularly changes the structure of your brain. The effects become noticeable after just a couple of days of practice, but for a truly lasting effect, meditation needs to become a habit. Using brain scans, brain researchers can detect the effects of meditation. When the surface noise in your brain calms down, your brain becomes very active in other respects. During meditation, the brain synchronises its activity and individual parts work together better. Overactivity in certain parts of the brain, such as the anxiety and stress centre (the amygdala) and the frontal cerebral cortex (the seat of the worrying voice) dies down, but other areas of the brain associated with sympathy, empathy, happiness, and creativity increase.

Here’s how to meditate

Do you want to give it a try, here and now, in the waiting room? In theory, it’s quite simple:

However pointless this exercise may seem, what you have done is nothing less than going through the emergency exit out of your mental misery. That is more than just wishy-washy mumbo-jumbo. Being attentive to your direct sensory perception also means breaking through the inner monologue – that inner voice that sometimes makes you happy, but just as often makes you suffer. Just realising that this back door exists allows you to stop being a slave to that voice.

If you want to do yourself a favour, it is useful to try practising meditation for some time. While not a panacea, it can provide an oasis of calm in this hectic, chaotic world over which we have little control. Research shows that just 12 minutes a day can have a very positive effect.

Humans are the only animal capable of thinking about the past and the future. This talent for looking ahead and planning gives us more power and control over our fate than other species, but the price we pay for this time perception is that we can also be chronically worried and unhappy. If we don’t learn how to rein in our creative mind, our thoughts very quickly start playing tricks on us.

Even if we’re sitting on the sofa with a warm blanket and our favourite beverage, we can become totally upset merely due to our thoughts. With a little bit of effort, you can think up an endless number of horrific scenarios for things that could go wrong tomorrow. Maybe the milk has dangerous bacteria in it. The neighbour’s house might catch fire. You might get sacked from your job tomorrow.

And to make things worse, you can’t just switch off your stream of thoughts as you would your TV set. You actually have little control over that. Just like the sounds you hear and the things you see, your thoughts aren’t something you choose. They come and go the whole day long, interrupted only by sleep. A worrier will recognise this situation.

With some people, worrying can intensify so much that it leads to chronic stress, symptoms of exhaustion, and panic attacks. Psychologists refer to this as generalised anxiety disorder. The problem is usually not the environment but a brain gone wild and running in circles because there is no quick and ready solution. Many of life’s problems have no quick and ready solution. Will I still have a job tomorrow? Does my partner still love me? Do I still love my partner? Will I still be healthy tomorrow?

You can go on worrying about these sorts of issues eternally, but you’ll never get a satisfying answer to them. Our brain needs certainty, but life itself is one big pile of uncertainty. No one knows what tomorrow will bring.

The key question is: Can you learn to relax and enjoy yourself while being conscious of the fact that the future is uncertain and that life can hit you hard at times? Is there a technique for dealing with uncertainty better?

To make unpleasant and boring moments pass by more quickly, most people seek out distraction. They kill their boredom by playing a game on their smartphone or exercising. Distraction works fine for ‘light’ suffering, such as boredom or an aching back, but with major uncertainty or serious pain it doesn’t work so well. The pain demands your attention and doesn’t just let you chase it out of your consciousness. With acute physical pain, you can resort to any number of painkillers, but the drug therapy route is more controversial when applied to psychological pain. You can take tranquillisers or numb yourself with alcohol and drugs, but in the long run, the fleeting, addictive, and uncertain character of these substances creates more problems than they solve. Is there some way to approach psychological (and physical) pain without medications?

Illustration by Joost Stokhof

Illustration by Joost StokhofMeditation: the power of rediscovering the here and now

You might call mindfulness meditation spiritual, religious, or airy-fairy, but we can also approach meditation from a scientific perspective, detached from its Buddhist origins and mystical connotations. Those aspects are not actually necessary to demonstrate its value. From a scientific perspective the verdict is clear: meditation is good for almost everything, just like sleeping, eating healthy, and walking. People who have unprejudiced awareness of the here and now – that’s what mindfulness meditation is – are doing themselves a lot of good. More than thirty years of research shows that it makes normal people like you and me much less neurotic, stressed, and anxious. And thus, happier. The advance are both mental and physical and can improve quality of life in different areas—work, relationships, love, creativity, and health. It increases concentration, improves one’s memory, and eases chronic pain. For an ‘activity’ that many people would probably dismiss as useless and utterly boring, its effect is simply amazing.

How can it have such a great effect? It’s less mysterious than it might seem. It’s a matter of silencing that worried voice in your head.

Research shows that the average person spends about half of their waking hours mulling over things, daydreaming, and worrying. You recognise it from that voice in your head that is constantly talking to you. That inner monologue in which we spend our lives is also called the brain’s backup network: the brain’s default state when it isn’t busy with something specific, but is daydreaming, making comparisons, worrying, and fretting.

Research shows that it is precisely that uncontrolled, inner monologue that makes people unsatisfied, stressed, and unhappy and keeps them in that state. The more our brain is busy digging up the past or trying to control the future, the more our attention shifts to things that aren’t going well in our life (because they need attention).

By training your attention with mindfulness meditation you create a different relationship with your inner monologue. Meditation is not about forcing yourself to stop thinking; that doesn’t work. In a certain sense, meditation teaches you to detach yourself from thoughts (and from lines running parallel to them). Not by viewing your thoughts and feelings as intruders, but rather by seeing through their fleeting and unreal nature. Over time, recognising that distinction makes a world of difference.

Skilled practitioners of meditation can testify to this. Just as with any other skill or sport, perseverance is required before meditation becomes a habit and feels good. You can train your brain in the same way that you can train your muscles. Meditating regularly changes the structure of your brain. The effects become noticeable after just a couple of days of practice, but for a truly lasting effect, meditation needs to become a habit. Using brain scans, brain researchers can detect the effects of meditation. When the surface noise in your brain calms down, your brain becomes very active in other respects. During meditation, the brain synchronises its activity and individual parts work together better. Overactivity in certain parts of the brain, such as the anxiety and stress centre (the amygdala) and the frontal cerebral cortex (the seat of the worrying voice) dies down, but other areas of the brain associated with sympathy, empathy, happiness, and creativity increase.

Here’s how to meditate

Do you want to give it a try, here and now, in the waiting room? In theory, it’s quite simple:

With your back straight, sit in the most comfortable position possible.

Use the stopwatch on your smartphone and set it to 3 minutes.

Close your eyes, take a couple of deep breaths, and calmly enter the here and now. Listen to the noises around you and feel the sensations in your body. (Do you find it difficult to close your eyes? Then leave them open. Let your gaze rest on a spot in front of you.)

And now for the very core of meditation: without forcing yourself, try to focus your attention on your inhalation and exhalation. Every time you notice your thoughts wandering, turn your attention again to your breathing. And again. And again. Until the stopwatch goes off.

Let your breathing go on as naturally as possible. Feel how your breath automatically enters through your nostrils and how your stomach moves up and down. All you need to do is to pay attention to this.

As you focus your attention on your breathing, you will notice how noises, thoughts, sensations, feelings, and images come and go in your consciousness.

However pointless this exercise may seem, what you have done is nothing less than going through the emergency exit out of your mental misery. That is more than just wishy-washy mumbo-jumbo. Being attentive to your direct sensory perception also means breaking through the inner monologue – that inner voice that sometimes makes you happy, but just as often makes you suffer. Just realising that this back door exists allows you to stop being a slave to that voice.

If you want to do yourself a favour, it is useful to try practising meditation for some time. While not a panacea, it can provide an oasis of calm in this hectic, chaotic world over which we have little control. Research shows that just 12 minutes a day can have a very positive effect.

Being conscious of the now

Strictly speaking, you are always living in the now, even if you worry about the future or have a flashback from the past. A projection of the future or an old memory always occurs now. But your immediate consciousness of the now is also a manufactured experience, one slowed down by your brain. The present you are now experiencing occurs a few milliseconds later than when it really occurred and, according to psychologists, consists of at least of 150 milliseconds. It has the duration of a single thought: ‘I am now seeing a bird fly by.’ At that moment you realise what you are now experiencing. According to research, this ‘now’ experience can last as long as 20 seconds, but people feel the most comfortable with a ‘chunk of now’ of about three seconds.

More pleasant, faster, and more efficient

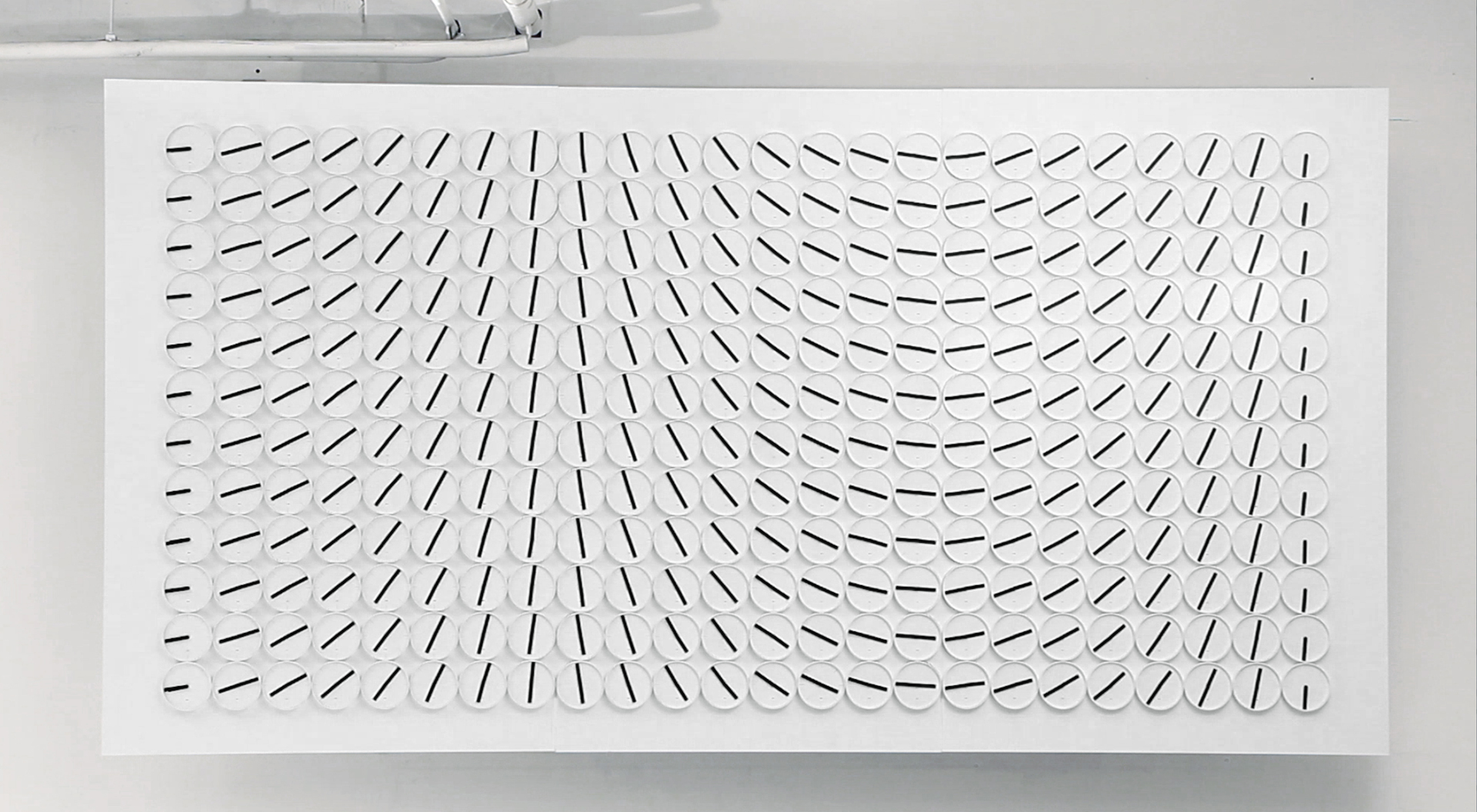

A million Times 288 by Humans since 1982, kinetic installation, 3440 x 1800 x 50 mm, aluminum, and electronic components, photography: Tim Meier, 2013. The kinetic installation consists of 288 clocks that are driven individually and display different patterns, drawings, texts, and numbers.

A million Times 288 by Humans since 1982, kinetic installation, 3440 x 1800 x 50 mm, aluminum, and electronic components, photography: Tim Meier, 2013. The kinetic installation consists of 288 clocks that are driven individually and display different patterns, drawings, texts, and numbers.Three ways to get more out of waiting

By Siba Sahabi

A Dutch citizen waits an average of 15,000 hours (1.7 years) over the course of their life. In the checkout line, on the phone with an information line, at the airport, or in a hospital waiting room. The so-called ‘waiting theory’ studies these situations with an eye to making the waiting process more pleasant.

What service can a hospital offer in a waiting room besides facilitating waiting in a practical way? While the time a patient spends in a waiting room may only seem to be a minor part of his or her overall experience in the hospital and with treatment, the subjective waiting experience can have a major effect on a patient’s well-being. Below you will find a few strategies that can help minimise patients’ uncertainty and ‘psychological’ waiting time.

Surveys and forms to prepare for talks with the physician

Some hospitals have their patients in the waiting room fill in simple questionnaires about their physical and mental health status. Some patients actually find it pleasant to answer difficult or sensitive questions first on paper before having their one-on-one talk with the doctor. This helps patients put their symptoms into words and also helps the doctor prepare before meeting the patient.

Information about what the patient can expect

Many patients want to know more about their illness and about diagnostic research and/or treatments but have difficulty looking for appropriate sources of information. By using brochures, hospital magazines, and digital media, hospitals provide their patients with information about various medical issues. (Educational posters can be perceived by patients as confrontational and unpleasant.)

Waiting room managers who help orient patients

Some hospitals employ so-called ‘waiting room managers’. These employees do things like assist patients in selecting the right brochures and filling in the surveys and function as a point of contact for various questions and remarks.

A million Times 288 by Humans since 1982, photography: Tim Meier

A million Times 288 by Humans since 1982, photography: Tim MeierThese three methods and services keep the patient busy while waiting for the doctor, making the time pass by more quickly and pleasantly. These methods can also minimise the negative feelings that some patients experience in waiting rooms, such as powerlessness and passivity. And finally, the methods also support communication between the doctor and the patient.