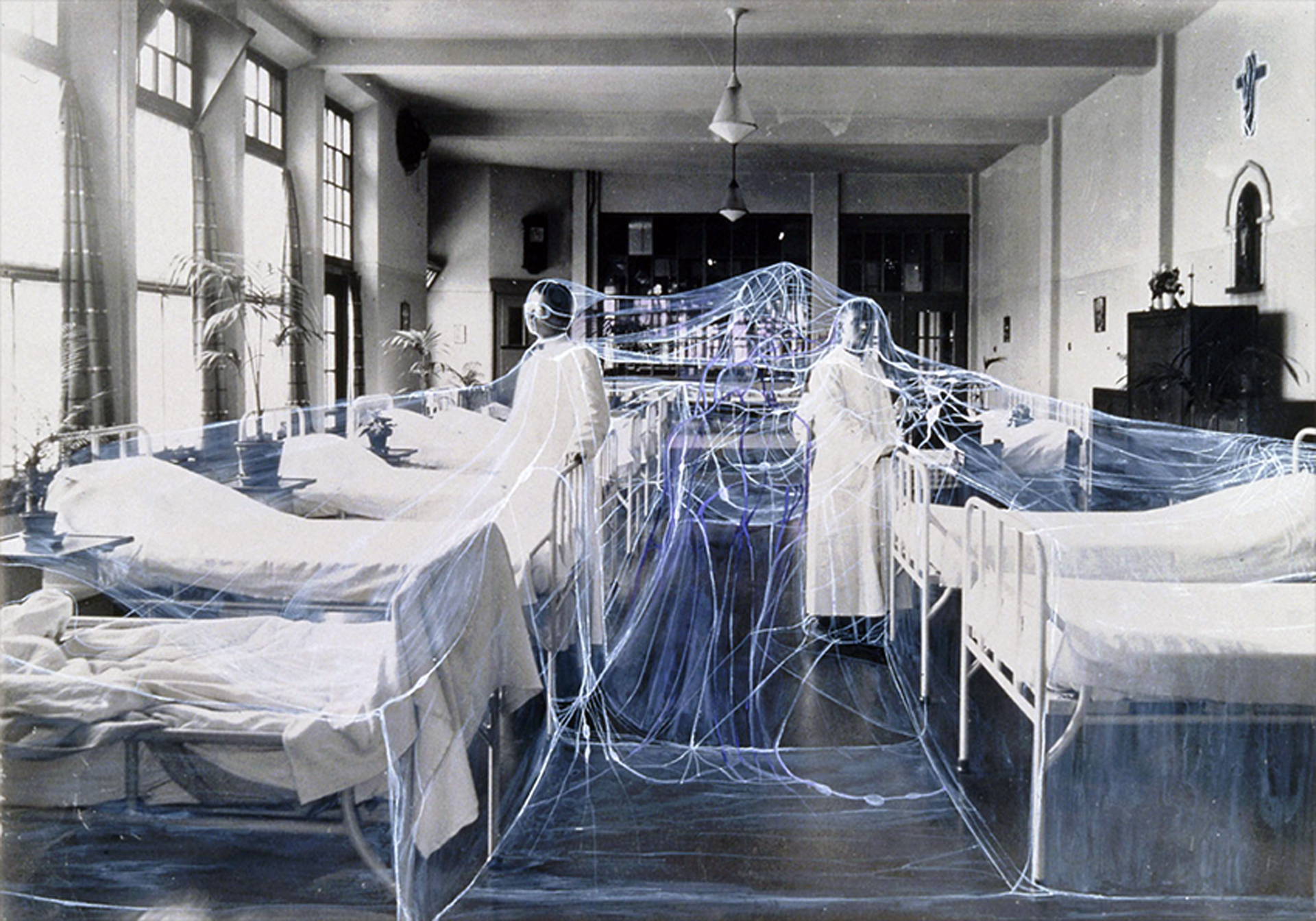

From poorhouse to modern hospital

By Siba Sahabi

Architectural historian Cor Wagenaar tells about the history and future of the hospital. ‘Hospital architecture is an instrument for stimulating positive experiences in the hospital.’

In 2006, I graduated from the Gerrit Rietveld Academy with work that included a project about the perception of time in hospitals. My project was supervised by Prof. Cor Wagenaar (1960). He is affiliated with the University of Groningen as an architectural historian and researcher. He is also the chief university lecturer for the chair in Architecture and History of Urban Planning at the Faculty of Architecture at TU Delft. Wagenaar has published various books and articles on topics including urban development and the architecture of healthcare.

Today, 13 years later, Wagenaar and I meet again in the Eerste Klas Restaurant at the central train station in Amsterdam. In this gorgeous setting with fin-de-siècle decor, Wagenaar speaks to me about the history of the European hospital.

What did the first hospitals actually look like?

‘Until the 19th century, hospitals served primarily as poorhouses. Due to gaps in medical knowledge, it was not possible to actually make this group of people better. These poorhouses were sponsored by the church and the city government in the name of charity and security. By putting the sick and the poor in homes, they were taken out of public view. The idea was that in that way they would not constitute a danger for the rest of society. These homes always had physicians involved, but they couldn’t actually do much for the patients.’

When did the situation change?

‘It was only in the 18th century that the idea arose of really curing people in the hospital and subsequently reintegrating them into society. Illnesses were not treated with medical interventions of the sort we are used to. Because knowledge was still limited at that time, treatment consisted largely of medicinal herbs and special diets, besides the well-known practice of letting blood. In the first generation of hospitals, the main issue was clean air. It was in this period that the so-called pavilion hospital model was developed, which consists of separate buildings in green surroundings.’

When were the first real medical interventions introduced?

‘In around 1850. That’s when surgery started being used. Surgery had already been used for a while in the military to remove bullets and amputate parts of the body. Surgery couldn’t do much more than that before 1850, but that all changed with the advent of two innovations: infection control and painkillers.’

‘It is difficult to imagine that our ancestors had to do without both of those things. Just imagine: before that time, you were operated on without anaesthesia, and if you survived the operation, you ran a tremendous risk of still dying from a deadly infection. After 1850, operations became a hospital activity that couldn’t be conducted elsewhere due to the specific equipment required. In this way, the hospital gradually evolved into a building with specially designed spaces. We can still recognise the operating room from these earlier hospitals. They resemble painting studios; in an operating room you need daylight with large windows facing north.’

When was medical technology introduced?

‘That happened in approximately 1900 with the invention of the X-ray machine. The X-ray machine was a revolutionary invention. From that time on we could also look into a living body. Before then, the most that physicians could do was to dissect corpses to study what exactly was going on in a body. What you could see with those first machines was still rather limited, but you were able to detect broken bones.’

‘From that point on, the hospital really became a medical stronghold. The new methods of treatment also created a new clientele: up until then hospitals were only for the poor. Before 1900, the rich would simply have the doctor come to their home, but now they had to go to a hospital to benefit from the medical treatments. Medical treatment also became increasingly complex and expensive, something the poor could not afford. The hospital gradually became an institution for people with money.’

When did the hospital become accessible for the poor again?

‘The construction of the welfare state made medical care accessible for all members of society again. That was a gradual process that began in the late 19th century and continued through the 20th century. Social insurance made money available so that poor people could also be treated in hospitals. That led to an explosive increase in hospitalisations, which further led to an explosion in the construction of new hospitals.’

What has characterised hospital architecture since the 19th century?

‘These buildings represented medical science, and medical science increasingly stood for rationality and opposition to religion and superstition. From 1900, medical science viewed a sick person as a broken mechanism that needed to be “repaired”. In the 1950s, psychology also became important due to the discovery of the negative effect that stress has on health. But these new insights still had little impact on hospital architecture.’

When did that change?

‘In the 1980s, Roger S. Ulrich figured out that there is a direct relation between how people feel and the medical outcome. Ulrich’s research included work on the view from a patient’s room and the healing process. For example, if you see nature, you will heal more quickly and need fewer painkillers and medicines.

Physicians viewed these studies with scepticism because they considered them to be a step backwards. But in spite of the initial resistance, it is without a doubt that Roger ushered in a new medical era. Since that time, more research has been done on the negative influence of stress and anxiety on the development and curing of diseases.’

What values characterise contemporary hospital architecture?

‘The “Evidence-based Design” movement establishes a relation between architecture and experience. Hospital architecture is an instrument for stimulating positive experiences in the hospital. We have now reached this stage. Hospitals now want to distinguish themselves with good architecture again and to stop thinking of themselves as “machines”. And all the top contemporary architects are now involved in hospital projects. Before, architects had been brought in as “artists” for special buildings, but not for functional hospitals. And the architects themselves had little interest in designing hospitals, but fortunately that has since changed. All the most important contemporary architects have now discovered hospital architecture. Now it is even a matter of prestige to design a hospital.’

What can you say about hospital architecture of the future?

‘You can sum it up in three words: normalisation, downscaling, and efficiency. And downscaling also includes fewer hospitals with fewer beds.’

And what does the waiting room of the future look like?

‘With the help of modern technology, waiting rooms right near the place of treatment will become redundant. In the future, patients will be kept up-to-date on the waiting time over their smartphones. In that way, they will be able to spend their waiting time outside the hospital. That gives the patient more control and autonomy. In the future, more and more waiting rooms will disappear.’