How do you minimise the contrast between the hospital and home?

By Siba Sahabi

A stationary hospital stay averages four days, or 96 hours. A patient spends 90 hours of this time resting, recovering, and waiting to be released. Just six of those hours are spent on treatment. So you could say that a patient room is also a waiting room. How can this waiting room be optimally furnished to promote the patient’s well-being?

Plea for a single-occupant room

Anyone who has ever gone through a hospital stay for a few days knows how difficult it can be to share a patient room. Sharing the room entails limiting privacy and comfort. Just when you are at your most vulnerable, you are forced to deal with having strangers in your immediate surroundings. Conversations with hospital staff leave no way to avoid sharing privacy-sensitive, and perhaps even embarrassing, information. To limit expenses and save space and waiting time, men and women are regularly placed together in a single room. Even four-occupant rooms are still quite common.

Single-occupant rooms are often only offered when they are medically necessary, such as when there is a risk of infection. But do unisex multi-occupant rooms belong in the 21st century? The 2015 study ‘One size fits all?’ by Jill Maben and colleagues shows that two thirds of all patients would rather be in a single-occupant room. They don’t have as much company that way, but they are fine with that. Fortunately, the trend in the construction of new hospitals is to provide more single-occupant rooms.

Peace and quiet

In a single-occupant room, patients are not bothered by snoring roommates, the alarm on their intravenous drip, or conversations between their neighbours, nurses, and visitors. Waking up well rested contributes to one’s well-being, and plenty of sleep is quite important for recovery.

Light and temperature

Do you prefer to sleep with the window open or closed? Do you like your room pitch-black or would you rather be caressed by sunrays? To feel as at home as possible, you also want to be in control of the temperature, ventilation, and lighting in your room.

Communication

A single-occupant room is more tranquil during doctor-patient conversations, which is conducive to better communication. Privacy-sensitive information stays between the doctor and the patient, supporting the sense of dignity. Patients feel safer if they can see hospital employees in the hallway from their bed and can interact with them.

Visual tranquillity

Clinical equipment makes people think of physical defects. If equipment is not being used, it’s more pleasant for patients if it’s put out of view.

Accommodating relatives and loved ones

Who would you most like to have around you to keep you from feeling isolated at the hospital? Being able to converse with your family and friends like you would at the dinner table minimises the difference between a hospital stay and everyday life. Social support from those close to you can greatly facilitate the recovery process and help take your mind off of your pain. Close friends and relatives can relate to the patient emotionally and offer advice and practical support, reducing the workload of hospital staff. For this reason it is important that friends and family members feel welcome and involved at the hospital. That requires sufficient space and facilities, such as enough chairs, a comfortable sitting area, a work table, and even a sofa bed to spend the night on if necessary.

A nice extra would be a laundry service in the hospital. This would relieve those close to the patient who normally take this task upon themselves.

Connection with everyday life

Nothing reduces stress like the feeling of being at home, sleeping under your own blanket. How about waking up and seeing the same painting that you would normally see on the wall at home? That can make an impersonal hospital room feel more like home.

The freedom to conduct daily rituals minimises the contrast between a hospital stay and your normal life. Reading your favourite newspaper, contact with colleagues and schoolmates, listening to your favourite music, watching your favourite news programmes, films, or series—preferably using speakers and not wearing headphones. A pantry so you can make a cup of tea or coffee and a small fridge stocked with drinks or little snacks makes things feel more homey. And a locker reduces the risk of losing one’s belongings.

Of course, these latter features can also be found in a hotel room. That is not so strange, because a stay in a hotel room gives more positive associations than a patient room with an institutional character. Research by Prevosth and Van der Voordt from 2011 shows that patients who stayed in a hotel-like patient room perceived their treatment as more positive. They valued the physicians, food, and hygiene more greatly than patients who stayed in a sterile hospital room. A hotel room should also have pleasant acoustics and a harmonious composition of colours, textures, materials, and shapes. There is often also art hanging on the wall. The interior is calming, positive, and varied without overstimulation. The ideal patient room is large and looks out on nature.

Sunlight

Research shows that patients recover more quickly in a sunny room. A 1998 study by H. Rubin and colleagues showed that female patients are particularly sensitive to light and had an average stay of 2.3 days in a sunny room, compared to 3.3 days in a gloomy room.

Conclusion

Beautiful surroundings, the presence of family and friends, and support with carrying out daily rituals all stimulate positive thoughts and hope. A positive mindset can reduce the need for painkillers and speed up recovery. Not only is a shorter hospital stay good for the patient, it also entails savings on healthcare costs.

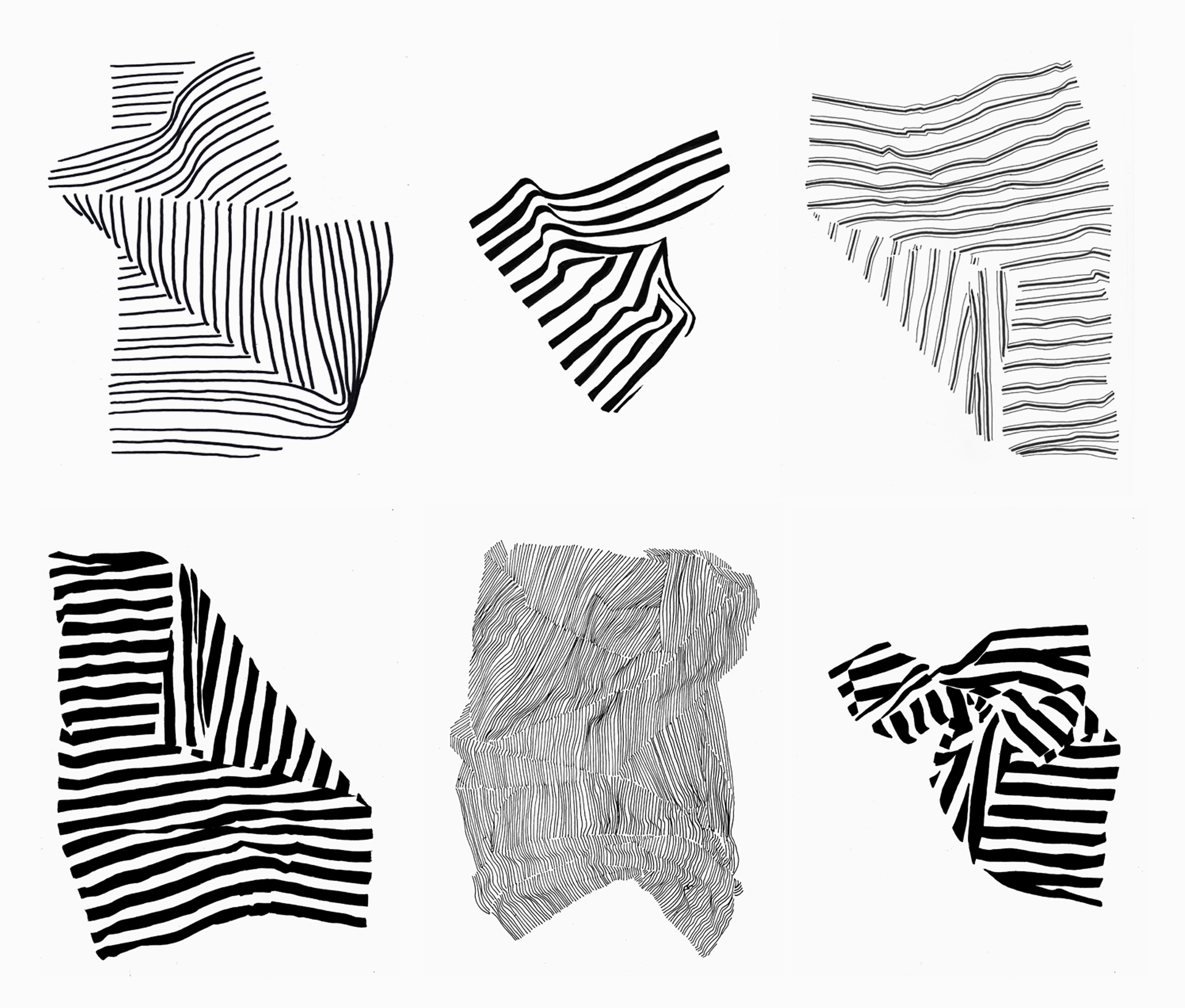

Sketches of sheets by Sanne van de Goor, 2019

Sketches of sheets by Sanne van de Goor, 2019